Gregory, David, 1659-1708 (professor of mathematics, University of Edinburgh, and Savilian Professor of Astronomy, University of Oxford)

Biography

David Gregory (1659-1708), astronomer and mathematician, was the first university professor to teach astronomy in the language of Newtonian gravitation. He is famous for his influential textbook, Astronomiae Physicae et Geometricae Elementa, (1702). Having studied a while at Marischal College, Aberdeen, and without graduating, Gregory took the Mathematics Chair at Edinburgh University in 1683, by unseating the incumbent there in a series of public debates. It helped that the chair had been occupied briefly some years before by his esteemed uncle, James Gregorie (1638-1675). David was awarded a hasty MA for decorum's sake, even though he had never studied in Edinburgh, and taught for seven years. His lecture notes show that he covered a broad range of subjects, some of them not in mathematics. He also taught a little optics, mechanics, hydrostatics, and even anatomy, from Galen. His first significant publication was in 1684, the Exercitatio geometrica de dimensione figurarum , in which he extended his uncle's work on the method of quadratures by infinite series.

In 1689 there sprang bad blood between the university masters and their paymasters, the city council, initially having to do with pay cuts and treacherous electioneering. There quickly developed a web of sleights and grudges, in the course of which Gregory was libelled before the new Hanoverian committee of visitation as it toured all the Scottish educational bodies following the recent change of government. He was said to be a violent, drunken atheist, who kept women in his chambers and once visited a prisoner in the Canongate tollbooth; worse, he was a superficial teacher and a crypto-Cartesian. Surrounded by influential friends, and not holding any demonstrably radical views in politics, science, or deportment, he was finally not dismissed from the faculty as many of his colleagues were, nor even required to swear the oath of allegiance to the Hanoverian monarchy or the religious Confession of Faith either.

Yet by 1691 he saw fit to cadge a fresh appointment comfortably far away, in Oxford. This was the Savilian Chair of Astronomy. In its pursuit he came to know personally the figures with whom he had lately been in professional correspondence, like Isaac Newton (1642-1727), Edmond Halley (1656-1742), and John Flamsteed (1646-1719), the first Astronomer Royal. He was given another MA to suit the post, and a desultory MD; he was elected to the Royal Society, and appointed a master commoner of Balliol College. He spent the rest of his life as Savilian Professor, where he became something of an evangelist for Newtonian science among the Cartesians. He even troubled to travel to the continent, to exchange views with prominent colleagues like Jan Hudde (1628-1704) and Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695). He quarrelled occasionally with Newton and Halley over various points of research, and with Flamsteed over tutoring maths in the Duke of Gloucester's household, but generally carried on very productively.

His Edinburgh lectures he retooled by 1695 into the enduringly influential optics textbook, Catoptricae et dioptricae sphaericae elementa, whose special contribution was to propose an achromatic telescope, whose combined lenses ought to counteract colour aberrations. By 1702 his principle work went to press, the remarkable Astronomiae physicae et geometricae elementa. This was the first textbook to cast astronomy completely in the alloy of Newtonian gravitational principles. Newton himself assisted with the work, which at least one publisher immodestly declared would 'last as long as the sun and the moon'. It certainly lasted most of the eighteenth century. His final big publication was a joint edition of Euclid, which appeared in 1703. All through his career he complemented his monographs with a steady flow of journal articles and published correspondence in mathematics and astronomy; his special interests included the catenary curve, eclipses, the contemporary 'parallax problem', and the very famous Cassinian orbital model for heavenly bodies.

Late in his life, in 1707, the Act of Union between Scotland and England effectively ended Gregory's studies, calling him away from his work on an edition of Apollonius (eventually finished by Halley), and setting him to work instead on rationalising the Scottish Mint, even as Newton was doing at the London Mint, and on calculating the enormously complex 'Equivalent', a payment to Scotland to offset new customs and excise duties. His health failed him during his extensive official travelling. David Gregory died in a Maidenhead inn a year later. David Gregory was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1692 and was made honorary fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh in 1705.

Found in 147 Collections and/or Records:

Notata phys: et math: London ..., 1697

Notes on scientific matters, many of them discussed with Newton, such as why the brachistochrone curve is a cycloid and how a musical chord can have the figure of a catenaria, and a record of curiosities, such as the toads of Surinam, who breed their young on their backs, and floors that can be secured made with dovetails instead of nails.

Notata phys: et math: London ..., 1698-1705

Almost certainly a latter part of Gregory's item 80: 'Notata Phys: et Math: D.G. Lond: 25 June &c 1698'. This covers cone sections, elements of Euclid, errata in a Halley treatment of comets in his own Apollonius project, and a jotting on Scottish history bibliography.

Notes on priority, 1707

This small slip bears what appears to be ammunition in Gregory's defence of his uncle James Gregorie against old charges of plagiarism. The confusing reference to "Actis Phil. Septemb. & Decemb. 1797" is a slip of the pen. The material appeared in the Acta of 1707.

Observ: Eclipsos Lunaris Oxon 19 Octr 1697 et [Mercury] in [the Sun] 24 Oct 1697, October 1697, with 2 apparently attached documents from 17041693

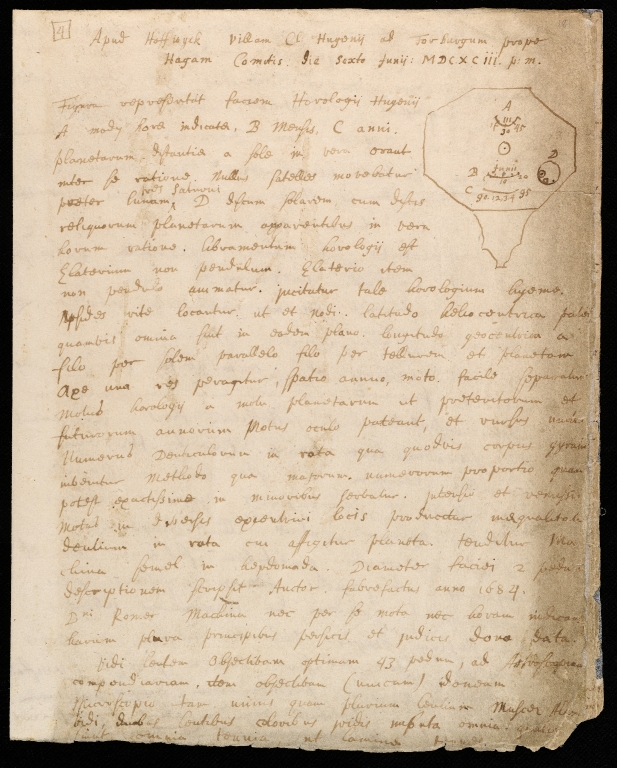

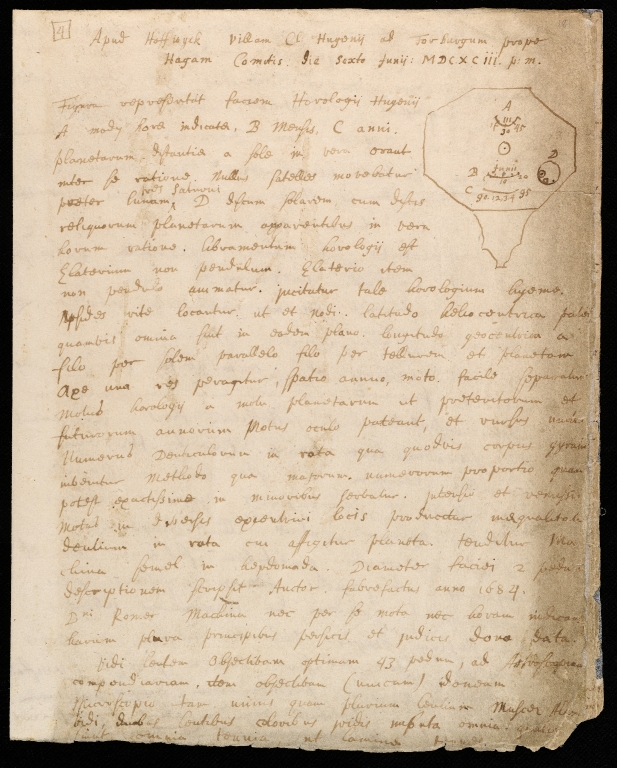

Observata et dicta apud D. Hugenium, 06 June 1693

Notes of a conversation in Holland with Christian Huygens, concerning an 'horologium' to show hours, months, years, and planetary positions. More general mention of the work of numerous other scientists: Notably, Huygens disputes the notion of John Bernoulli (James Bernoulli's younger brother) that the curve of an inflated sail is part-catenary and part-circle, and warns that Newton ought not to be 'deflected' into theology or chemistry.

Oratio de Mundi systemate contra Cartesiones, 1690

Graduation speech, in Gregory's hand, of one John Falconer. This young man may have been related to the Falconer who secured Lord Tarbat's interest for Gregory over the dreaded Visitation.

Oratio de Quadr: Lunale Hypocratis, 1690

Graduation speech, in Gregory's hand, of one Laurence Oliphant. This young man may have been Gregory's future brother-in-law.

The subject is Hyppocrates' lunula. Two documents on the same subject come before this, no doubt as supporting notes. One is the draft of a letter from Gregory to Wallis, referring to a 1687 article by Tchirnhausen in the Leipzig Acta, the other, a transcript of that article.

Ordo in Mathes. docenda..., 1697

An address in Balliol College about how mathematics should be taught.

Papers of David Gregory

Pars Probl: veterum, 28 August 1680

Gregory's solution to a very ancient problem about parabolae and their asymtotes.

Filtered By

- Subject: Mathematics X

Additional filters:

- Type

- Archival Object 145

- Collection 2

- Subject

- Physics 14

- Astronomy 13

- Optics 12

- Curves 7

- Geometry 7

- Oxford Oxfordshire England 6

- Bibliography 5

- Edinburgh -- Scotland 5

- Gravity 5

- Amsterdam (Netherlands) 4

- Curves, Rectification and Quadrature 4

- Horology 4

- Netherlands 4

- Algebra 3

- Astrophysics 3

- Catenary 3

- Sphere 3

- Comets 2

- Mechanics 2

- Medicine 2

- Planets 2

- Refraction 2

- Abnormalities, Human 1

- Achromatic Telescope 1

- Aging 1

- Amortization 1

- Anatomy 1

- Authors and Publishers 1

- Blood, Circulation 1

- Catapult 1

- Celestial Mechanics 1

- Centrifugal Force 1

- Centripetal Force 1

- Chemistry 1

- Church of Scotland, Establishment and disestablishment 1

- Circle 1

- Classical Literature 1

- Coal Mines and Mining 1

- Copper Mines and Mining 1

- Dynamics 1

- Eclipses 1

- Economics 1

- Ellipse 1

- England 1

- Flanders 1

- Flood, Biblical 1

- Geodesy 1

- Geodetic Astronomy 1

- Geometry, Elemental 1

- Glasgow Lanarkshire Scotland 1

- Hamburg (Germany) 1

- Lectures and Lecturing 1

- Leiden (Netherlands) 1

- London (England) 1

- Lunar Theory 1

- Magnetism 1

- Motion Study 1

- Neath (Wales) 1

- Numerical Integration 1

- Pendulum 1

- Philosophy 1

- Politics 1

- Professional Criticism 1

- Quadratures 1

- Scotland, History, The Union, 1707 1

- Ships 1

- Tariff 1

- Wales 1

- Wales, History, 1536-1700 1 + ∧ less